Coming hot on the heels of the ECB’s climate change stress tests, Evergrande’s threatened default and possible debt restructuring expose some of the high-level challenges that may arise when economic policy seeks to counter the effects of unbridled expansion on environmental degradation.

“Where on earth are you getting that from?” you might well ask.

First, let’s be clear that Chinese policy concern over excessive debt accumulation long pre-dates the country’s recent decision to target net zero emissions. Entirely separate rationales can be identified for addressing the two problems; in particular, Kenneth Rogoff and Yuanchen Yang have recently exposed the stretched valuations in the Chinese housing sector based purely on conventional indicators.

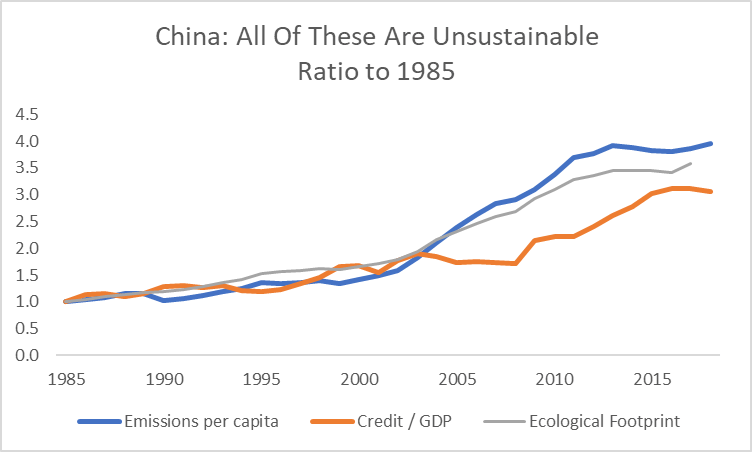

Second, China is far from unique in the combination of increased indebtedness and an unsustainable ecological footprint. What makes it particularly striking is the rapidity and extent with which the two have developed. For example, Chinese nonfinancial corporate debt/GDP almost doubled from an already elevated 110% of GDP in the decade after 2007. Periods of accelerated debt accumulation are often associated with credit being extended further and faster than systems of governance, regulation or even market evaluation can keep up, increasing the chances of debt stress later.

Despite these caveats, the reason for linking Evergrande with the ECB’s stress tests is the dual sources of leverage that have developed in China’s economy over the last twenty years: rapid economic expansion required the financing of large capex increases and encouraged expectations of future growth to become embedded in credit provision while, at the same time, the growth itself overloaded the country’s environmental capacity to sustain it, as shown in Global Footprint Network’s measure of China’s net biocapacity.

In cases like this, where assets are initially valued and credit allocated on the basis that the environment is a free resource, the imposition of an environmental constraint to economic activity through a policy target to reverse some form of environmental degradation may easily undermine the income and revenue expectations on which credit was provided. Moreover, the affected sectors need not be those most directly related to the policy constraint, but instead may be the ones where the build-up in debt was the largest and hence the likely sensitivity to changes in growth expectations highest.

The implication is clear: stress tests like those performed by the ECB that presume a VAT hike can be used to mimic the effects of a change in relative pricing may miss the (possibly more significant) system-wide nature of the economic adjustment to changes in economic and environmental constraints.

Viewed from a market practitioner’s perspective, conventional measures of financial leverage need to be enhanced to incorporate implicit environmental leverage, for example, through a measure of the beta of indebtedness at a corporate or sectoral level to emissions or environmental degradation. In practice, the most desirable measures of environmental degradation would be those most closely linked to that targeted for tighter environmental regulation.

To demonstrate with an example for China, we use an OECD report on sectoral debt accumulation and leverage, showing in the chart below a measure of the 5 year rolling sensitivity of leverage in selected sectors to increases in the level of environmental degradation.

This exploration of implied financial leverage to the environment is very different from standard approaches to evaluating stranded asset risk which consider the scope for physical infrastructure to become unusable in the event that a binding carbon budget is imposed. Nonetheless, the underlying mechanism is the same – an environmental constraint is imposed which had not been factored into market expectations – and the applications to the assessment of market risk pricing are potentially significant as we enter a period where governmental environmental policy changes rapidly such that environmental constraints increase.