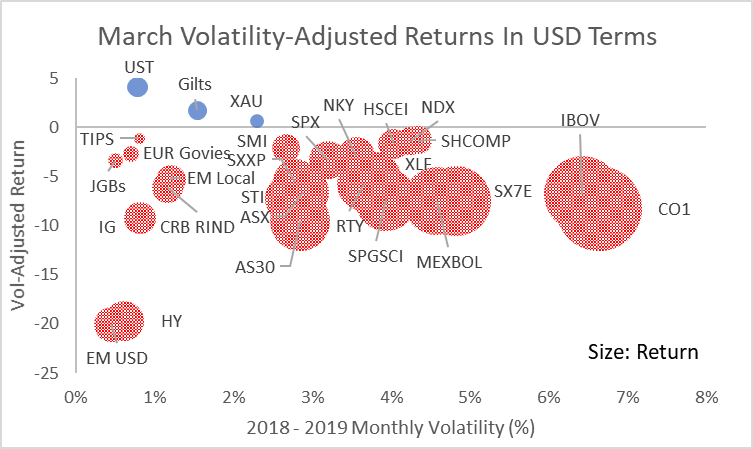

Two charts summarise the extreme destruction of value seen in March.

The first chart shows the local currency returns of a selected sample of assets across fixed income, equities and commodities. Fixed income returns are from Barclays’ indices, while all other assets are shown with their Bloomberg tickers for convenience. Returns shown are in local currency terms (in USD for commodities).

The chart reveals two key features of March’s shock:

- The imbalance between the number of assets generating positive returns and those suffering losses: safe havens were few and far between and, for the month as a whole, provided a very modest offset against the losses elsewhere;

- The severity of the losses for commodities and commodity producers, bank stocks as well as cyclical assets which had been priced for growth (eg RTY: the Russell 2000).

The absolute scale of the losses is, of course, dramatic, but the source of the shock to portfolios is best seen when adjusting for the normal volatility of each asset. In this case, we show all returns from the perspective of a USD-based investor (converting foreign currency assets on an unhedged basis) using monthly volatility through the 2018-2019 period as indicative of the type of risk an investor might normally have expected from each asset.

- Although, the March shock was crushing for high volatility assets like oil, Mexican and Brazilian equities, on a volatility-adjusted basis it was significantly worse for USD-denominated high-yielding credit assets;

- Credit shocks of this sort often take time to fully dissipate through the financial system. The initial wave of price destruction leaves anomalies in relative pricing that correct over weeks or possibly months;

- In these circumstances, it can be helpful to consider the conditional price of an asset, eg if credit spreads accurately discount the risk of defaults, where should equities trade to balance risk-adjusted expected returns?

The commentary contained in the above article does not constitute an offer or a solicitation, or a recommendation to implement or liquidate an investment or to carry out any other transaction. It should not be used as a basis for any investment decision or other decision. Any investment decision should be based on appropriate professional advice specific to your needs.