The first set of recommendations from economists in response to the COVID-19 crisis saw a broad consensus that can be summarized as:

- Act fast,

- Do whatever it takes,

- ‘Flatten the recession curve’ [Baldwin and di Mauro, 2020].

In the midst of a very broad range of possible outcomes, the debate on how to foster a sustainable recovery has been striking for the prominence of policies with the double merit of boosting growth and the economy’s capacity to grow whilst reducing CO2 emissions. The below summarises the main themes with a slight bias towards the UK, but with broad application.

The impact of the crisis

All crises leave scars:

- Balance sheets: the accumulation of debt by governments, businesses and households is inevitable; the presumption is that in contrast to the post-2008 crisis, governments will seek to grow out of the current / coming debt accumulation or perhaps find new approaches to taxation rather than repeat the post-2008 spending restraints that tended to exacerbate inequalities [Haldane in Stern et al, Strategy…, 2020];

- Behavioural: absent strong direction from the public sector, the expectation is of a highly conservative private sector response to the shock (increased desired savings, etc) [Haldane, ibid];

- Changed social contract [Chater and Delaney in Chater et al, 2020] with increased concern over how people are disconnected from society [Larden in Chater et al, 2020];

- Complex systems that have been ‘jumbled up’ are unlikely to return to their previous state [Hahn in Chater et al, 2020].

In no way was this a typical economic downturn:

- Deliberate inducement of the recession for public health purposes [Tenrayo in Velasco et al, 2020];

- Simultaneous implementation of programmes to stabilize businesses through loans, cushion income losses, prevent normal creditor reactions to credit payment interruptions and preserve worker-firm matches [Blundell, 2020] as well as massive monetary stimulus to underpin liquidity;

- Very little moral hazard [Tirole, 2020]

COVID-19 likely to exacerbate existing inequalities and create new ones:

- Inequalities were evident in many economies across, for example, income, education, race, sex [focusing on the UK as an example, Blundell, ibid]. In the US, as a less frequently observed example, suicide risk since 1995 has increased ‘almost exclusively’ amongst those without a college degree [Deaton, 2020];

- Healthcare inequalities and social insurance limitations act as a fault-line in the US [Stiglitz, 2020];

- Access to education has been highly (undesirably) stratified during the lockdown, with likely long-lasting impacts [Blundell, ibid];

- In developing countries, there is a clear risk of undoing a decade of progress in taking people out of poverty and a possibility that the lockdowns have as severe an effect on health as the virus itself [Khan in Velasco et al, 2020].

Increased incentives to substitute Capital for Labour:

- The digital investment catalyst ‘just happened,’ reflecting the inability to run businesses in its absence [Haldane, ibid];

- Reassessment of the infrastructure and management costs needed to support office-based and home-working as well as the expectation of increased illness [Haldane, ibid];

- Expect a significantly negative impact on social mobility, with a high priority for policy to prevent new rounds of long-term unemployment [Machin in Stern et al, Policy… 2020];

- Aggressively subsidise labour demand as an immediate response [Velasco in Stern et al, Policy… 2020].

Policy constraints:

Expectations for policy constraints in the period after the immediate recovery:

- High public debt: whilst growing out of it sounds great, what is the policy mix that creates success where previously there has been none? In response to high debt, governments either raise taxes above spending or depress interest rates below growth rates [Reis in Velasco et al, 2020];

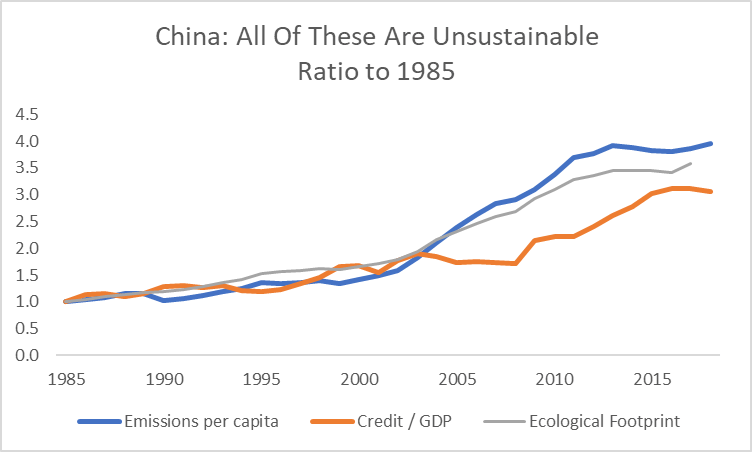

- Poor productivity: possible contributions through monopoly power (via under-investment) and the misallocation of investment (abundantly clearly through CO2 emissions, perhaps also zombie companies sustained by ultra-low interest rates) [Reis, ibid]

- Tirole [ibid] proposes five scenarios for the policy response to high debt:

- Run primary surplus;

- Restructure debt;

- Exceptional wealth taxes, either on households or (with high risk in the euro area) banks;

- Debt monetisation, with the risk of raising inequality through the impact of inflation on those without employment income or with only nominal assets as savings;

- Collaborative stimulus measures that

Policy Themes

Resilience

- Increasing resilience has to be a core policy focus [King, 2020];

- Address widespread policy myopia likely requiring increased investment at the expense of consumption [Tirole, ibid]

- Investment in social and institutional capital to deliver functional government [Zenghelis in Stern, Strategy… 2020] but not in a traditional centralized system [Rajan 2020; Coyle in Stern, Policy…, 2020];

- Public goods that are privatised become potential sources of fragility [Deaton ibid, Stiglitz ibid];

- Yet, the private sector can have a core role in enhancing resilience and public sector capacities [Romer, 2020] as witnessed by the contribution of private laboratories to greatly expand Germany’s testing capacity;

- ‘Reshoring’ does not equate to resilience [Tirole, ibid]

- Strengthen labour markets to cut short negative feedback loops:

- social insurance,

- skills agenda for green transition;

- human capital tax credits;

- improve demand/supply matching information/coordination in local labour markets [Blundell ibid, Machin ibid];

- Simply rebuilding businesses with pre-crisis exposure to climate change would be a catastrophic failure to improve resilience – see below.

‘Build back better’

- Stern et al’s motivation [Stern, Strategy…, 2020] for focusing policy efforts comes from an assessment of woeful productivity, inadequate investment, the experience of austerity as a catalyst / amplifier for increased inequality, regional inequalities, under-investment in natural and social capital as well as an emphasis on the labour skills required for the green transition;

- Survey responses compiled by Hepburn et al emphasise the desirability of five types of policy:

- Clean infrastructure;

- Building efficiency retrofits;

- Natural capital;

- Education and training;

- Clean R&D.

- For a discussion of building energy retrofits specifically and system complexity from an engineering perspective, more generally, see Mayfield 2020.

Accelerate investment required to render a sustainable recovery

- Directly targets the inadequacy of investment in the last cycle, provides an immediate source of demand stimulus and employment whilst also providing a CO2-reducing supply boost if correctly targeted [Zhengelis, ibid];

- IMF and OECD estimate investment multipliers of 2.5-3x the size of the initial investment [Llewellyn in Stern et al, Strategy…, 2020];

- Infrastructure investment has the capacity to crowd-in private sector investment through network effects and concentrate private sector expectations around climate change objectives in ways that other policies cannot [Grubb 2014, Zhengelis ibid];

- It can be combined with revenue-raising / redistributing policies that reinforce the shift to cut carbon emissions [Burke et al, 2020];

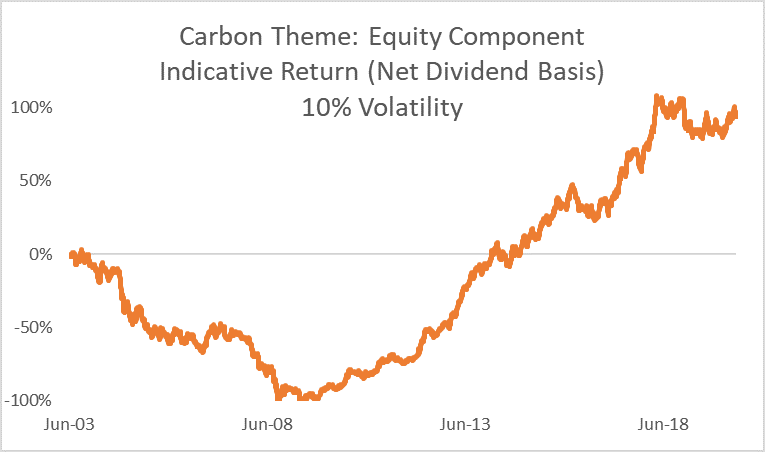

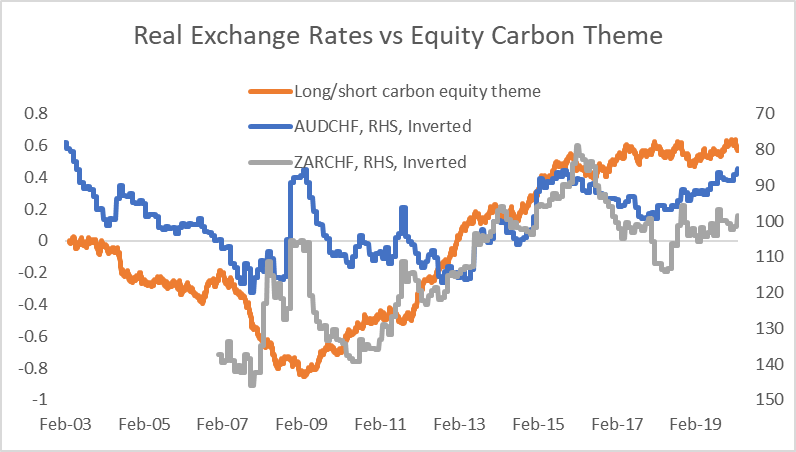

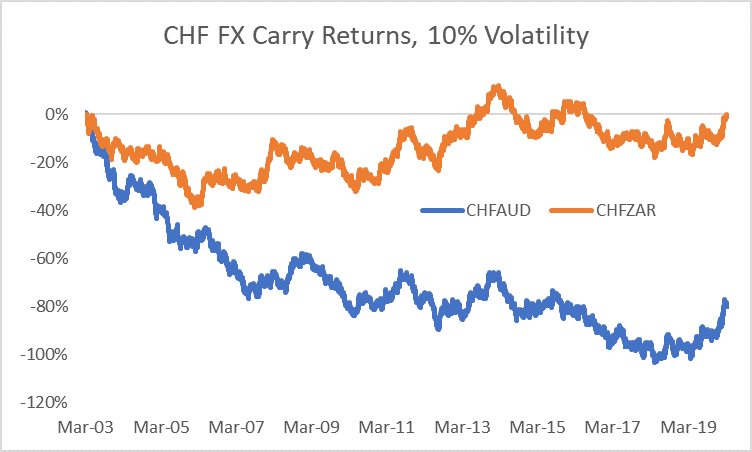

- It pushes on an open door in that the cost of capital has already shifted dramatically against carbon-intense activities.

Bibliography

P Aghion, C Hepburn, A Teytelboym, D Zenghelis, Path dependence and the economics of climate change, The New Climate Economy, 2020

R Baldwin, B Weder di Mauro et al, Mitigating the COVID Economics Crisis, 2020

R Blundell, Inequality and the COVID-19 crisis, Royal Economic Society webinar, 2020

J Burke, S Fankhauser, A Bowen, Pricing carbon during the economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, Grantham Research Institute Policy Brief, 2020

N Chater et al, Behavioural science in the context of great uncertainty, LSE webinar, 2020

A Deaton, Inequality and the COVID-19 crisis, Royal Economic Society webinar, 2020

H Doukas et al, Convergence between technological progress and sustainability is not that obvious, 2020

C Goodhart, M Pradhan, Future imperfect after Coronavirus, 2020

M Grubb, Planetary Economics, Routledge, 2014

C Hepburn et al: Will COVID-19 fiscal response packages accelerate or retard progress on climate change?, 2020

P Watkins et al, COVID-19 and de-globalisation, LSE webinar, 2020

M King, Radical Uncertainty, SPE podcast, 2020

M Mayfield, Climate Change: Hoping for the best, planning for the worst, webinar, 2020

P Romer, Conditional Optimism

P Romer, Roadmap to responsibly reopen America, 2020

R Rajan, How to save global capitalism from itself, Foreign Policy, 2020

J Stiglitz, Four priorities for pandemic relief efforts, Roosevelt Institute, 2020

N Stern et al, Strategy and investment for a strong and sustainable recovery, Royal Economic Society webinar, 2020

N Stern et al, Policy for a strong and sustainable recovery, Royal Economic Society webinar, 2020

N Stern et al, Finance for a strong and sustainable recovery, Royal Economic Society webinar, 2020

J Tirole, The short, medium and long run economic impact of the crisis, Royal Economic Society webinar, 2020

A Velasco et al, COVID-19: The economic policy response, LSE webinar, 2020